Hatching rates in Virginia red-cockaded woodpeckers

There are Still Wizards: A film

September 13, 2019

CCB team spends fifth spring with red knots along South Atlantic Coast

September 23, 2019By Bryan Watts

9/13/19

Woodpecker clutches are like a box of chocolates – you never know what you are going to get. Some years are all hat and no cattle with a large number of eggs produced early that turn out to be duds. Other years start out slow with relatively few eggs but those eggs produce and the season ends on a high. The whipsaw roller coaster ride is dramatic in Virginia, with hatching rates varying from less than 50% to more than 90% across years.

The red-cockaded woodpecker is federally endangered and the birds in Virginia represent the northernmost population throughout their range. Due to the rarity of these birds and the difficulty of tracking nests in cavities that are typically 30 to 60 feet high, we have known very little about their nesting ecology. The development of the peeper scope has allowed us to pull back the curtain on the intimate details of clutch size, hatching rates, and nestling mortality in Virginia woodpeckers. As part of a broader monitoring program, we have been able to follow 131 clutches through to fledging over the past few years. Details on these breeding attempts have begun to reveal some patterns.

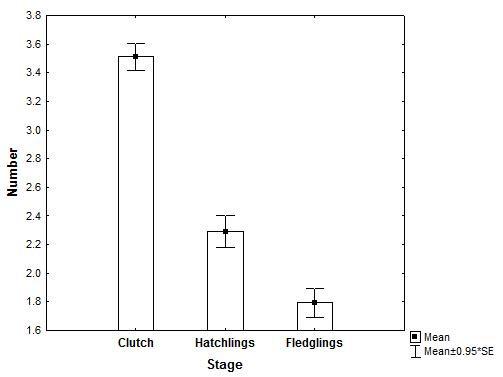

Loss of reproductive potential during both the egg and nestling period is high in Virginia. Hatching rate is the percentage of eggs laid that actually hatch. Brood reduction is the loss of birds from the time they hatch until the time they fledge. Mean clutch size is very high in Virginia at 3.51. This compares to reported values of 3.27 in North Carolina and 2.9 in central Florida and supports the long-held belief that the woodpecker, like many other birds, would exhibit a latitudinal gradient in clutch size. However, overall hatching rate in Virginia is a low 65.2% and survival of nestlings that hatch is 78.3%. The consequence of these patterns is that brood size at fledging is only 1.79. On average, it takes nearly two eggs to produce a single fledgling woodpecker.

Many factors have been advanced to explain both hatching rates and brood reduction in birds. Through various mechanisms, brood reduction allows for matching of brood size (demand) to the amount of food coming in (supply) to the cavity. The inability of pairs to provision larger broods may have to do with their experience, the number of helpers they have to assist, or the availability of resources in their territory. The pattern of brood reduction that we have observed in Virginia supports the notion that site quality varies between breeding groups. Territories fall into two camps, including sites that consistently fledge more than 80% of young that hatch and sites that consistently fledge less than 65% of young that hatch.

In a benchmark paper examining factors impacting hatching rates across many bird species, Walter Koenig identified sociality as one of the driving forces. He shows that hatching rate declines as sociality increases and suggests that social interference may play a role in reducing hatching rates. Red-cockaded woodpeckers exhibit a rare breeding strategy where breeding pairs often have multiple helpers that participate in cavity maintenance, brood rearing, and sometimes incubation. The species sits on the hyper-social end of the spectrum and Virginia has some of the largest groups of helpers throughout the range, likely due to limited habitat availability. Social interference may play a role in the exceptionally low hatching rates for Virginia woodpeckers. The territory with the lowest hatching rate (52%) has consistently carried 8-10 individuals into the breeding season.