Virginia woodpeckers have record year

Waterbird winners and losers – results of the 2018 survey

July 9, 2019

Assateague and Sable Islands – Bookends to Ipswich conservation

July 11, 2019 By Bryan Watts | bdwatt@wm.edu | (757) 221-2247

July 6, 2019

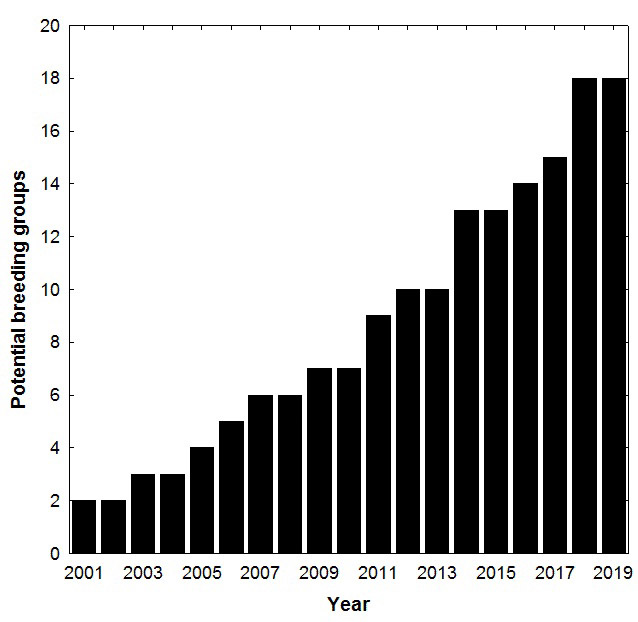

Red-cockaded woodpeckers in Virginia had a record-breaking breeding season in 2019, taking another step along their path to recovery. The population included a record 18 breeding groups for the second consecutive year, a number not documented since the 1970s. Pairs produced 29 fledglings including 20 females and 9 males. This is the highest number of young produced in Virginia in modern times. Just as significantly, pairs produced young on three properties including The Nature Conservancy’s Piney Grove Preserve (14 breeding groups), the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge (3 breeding groups), and the Virginia Department of Game & Inland Fisheries’ Big Woods Wildlife Management Area (1 breeding group) for the first time since the 1990s. This is the first breeding attempt ever documented within the newly created Big Woods WMA and a cause for great celebration.

Similar in appearance to downy and hairy woodpeckers that are widely recognized as common “backyard” birds, the red-cockaded woodpecker has a much more specialized ecology. Red-cockadeds require old-growth pines and are primarily associated with fire-maintained pine savannas of the Deep South. Red-cockaded woodpeckers in southeastern Virginia currently represent the northernmost population. Throughout the latter half of the twentieth century this population experienced a catastrophic decline, reaching a low of only two breeding groups by 2001. Heroic efforts over the past 20 years to save the species in the state have included improved forest management, the introduction of fire for hardwood management, the use of artificial cavities as bridges to natural cavity excavation, translocation of birds from other populations, and intensive management of cavity competitors. The fight has been a collaborative effort by a coalition of committed conservation partners. The success in 2019 is the last in a series of advancing population benchmarks suggesting that the partnership is doing something right.

The 2019 nesting season was the earliest we have ever recorded in Virginia, with eight pairs either completing or initiating clutches before 25 April. Everything just seemed to come together early for the birds. By season’s end, 17 of the 18 breeding groups made breeding attempts and 14 groups fledged young. Of 66 eggs that were followed through the breeding season, 45 (68.2%) hatched, 36 (54.5%) survived to banding age, and 29 (43.9%) fledged.

The Center for Conservation Biology will continue the annual monitoring of this population. The next scheduled activity will be the winter census where we will count and identify all individuals in the population to determine status and movements.