Losing ground to sea-level rise

Anhingas march north

August 23, 2018

Female peregrines under pressure

October 2, 2018By Bryan Watts | bdwatt@wm.edu | (757) 221-2247

September 26, 2018

They have names like Big Easter, Gull Marsh, and Egging Marsh – places where the early settlers of the Virginia Barrier Islands would go each spring to gather fresh eggs by the bushel baskets to carry over and sell to mainlanders. Like a loud traveling party, the laughing gulls would return to their marshes each April with their raucous calls andshowy flights. There is nothing shy or demure about a laughing gull. They nested in such dense colonies that it was easy work to collect hundreds of eggs in a morning.

Laughing gull in flight over a marsh along the seaside of the Delmarva Peninsula. Once the most abundant colonial waterbird in the marshes, the species is being forced to move to higher ground. Photo by Bryan Watts.

The unique voice and constant calls of laughing gulls have been a familiar part of life on the Eastern Shore. But over the past 15 years, many of the nesting marshes have gone silent. Like neighborhoods called “Bear Creek” or “Eagle Point” in the heart of our cities, the early attributions have become empty place names – names that seem oddly out of sync in the context of today.

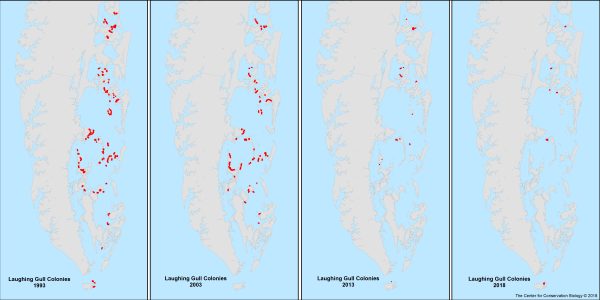

Time sequence of aerial surveys showing laughing gull colonies within marsh patches of the lower Delmarva Peninsula in Virginia. The footprint of these colonies has declined by 95% in a very short period of time. Data from CCB. (Click to see larger image.)

I first had the opportunity to survey these historic colonies from the air in the early 1990s. On 27 May, 1993 Mitchell Byrd, Fuzzzo Shermer, and I flew for seven hours back and forth over the expansive marshes of the seaside mapping and counting colonies. It took a day and a half to complete the survey. The larger colonies were beehives of activity that could be seen from miles away. From above, the colonies nearly glowed with nests and birds contrasting against the deep green marsh grass. On marsh islands the colonies were ringed like donuts where the birds built nests on rafts of wrack that had washed up along their perimeter. On the larger marshes colonies were on high shelves and had a worn look as though they had been used for hundreds of years. In a single round of surveys we tried to capture the series of colonies that had been known by generations of locals. In the moment, with the drone of the engine and the chaos that comes along with surveying in the air, we had no sense of an approaching cliff. Somehow things seemed as expected and the birds were going about their business as they had done for centuries.

Laughing gull nest in a marsh along the lower Delmarva Peninsula. Building taller and taller nests is a response to rising water. Gulls are now confined to high points within tidal marshes. Photo by Bryan Watts.

Laughing gull eggs in a marsh colony on the lower Delmarva Peninsula. These eggs were collected for use by generations of residents. Virtually all of these historic colonies are now gone due to sea-level rise. Photo by Bryan Watts.

We have had the privilege of conducting aerial surveys of the gull colonies approximately every five years since 1993 and have witnessed a rapid change since 2003. Virtually all of the historic marsh colonies where residents once collected eggs no longer support nesting gulls. From the air, I can still see the worn, high shelves in the marshes that are reminders of what once was. They appear like ghost towns where time and the beehive of activity have moved on. Between 1993 and 2018, the footprint of gull colonies on the lower marshes of the Eastern Shore coastal bay has declined from 326 hectares to only 15 hectares, a 95% decline. It is staggering to recognize that these historic colonies have disappeared over such a short period of time.

View of a laughing gull colony from the air. Once spread out in a ring around the periphery of marsh islands, colonies are now confined to small patches of higher ground. Photo by Bryan Watts.

Rising water and the increased frequency of inundation during high tides appear to have made these marshes unusable as breeding sites. Equally concerning is the fact that the marshes have supported a community of breeding species. Laughing gulls are visible occupants of the marsh patches and are easy to survey from the air. Other, more secretive marsh species including clapper rails, black rails, seaside sparrows, saltmarsh sparrows, willets, and American oystercatchers are no doubt suffering from the same tides and may also be increasingly vacating these historic habitats.