Urban herons hold their own

The fish factory

July 16, 2018

Up and down year for Virginia woodpeckers

July 17, 2018By Bryan Watts | bdwatt@wm.edu | (757) 221-2247

July 17, 2018

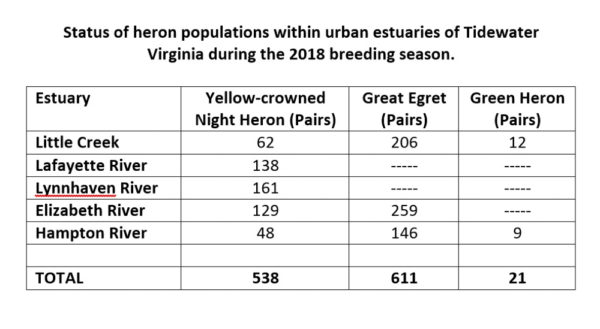

CCB biologists have monitored breeding herons within residential neighborhoods of tidewater Virginia (including the cities of Hampton, Newport News, Norfolk, Virginia Beach and Portsmouth) since the mid-1980s. As part of the 2018 Virginia colonial waterbird survey (funded by the Virginia Department of Game & Inland Fisheries, the Virginia Coastal Zone Management Program and CCB), residential neighborhoods, parks and other urban areas were once again surveyed for breeding herons. Despite the relentless efforts of homeowners to encourage the birds to move off of their properties, the birds continue to hold their own.

Green heron brood venturing out on a limb from the nest in Norfolk, Virginia. Green herons fly under the radar of homeowners and virtually none are aware that they host pairs. Due to their nesting behavior and substrate use, green herons are particularly difficult to survey. Photo by Bryan Watts.

Although 11 species of herons, egrets and ibises nest in Virginia, only three including yellow-crowned night herons, great egrets and green herons are tolerant enough of humans to nest in urban settings. Yellow-crowned night herons are the most widespread, nesting in neighborhoods that have stands of loblolly pines between 40 and 80 years old that are positioned around productive cordgrass marshes where they feed on crabs. Their breeding locations appear like halos around these marshes. Great egrets nest in the crowns of loblolly pine stands that are greater than 100 years old. Great egrets feed on fish and because they are capable of flying up to 20 miles to feed, their colonies may form just about anywhere in tidewater. Green herons typically nest in dense, low trees such as live oaks, willow oaks or crepe myrtles. Although they often nest in small colonies, isolated pairs also nest making them difficult to survey.

Male yellow-crowned night heron with a stick collected for nest building. Yellow-crowns pairs have more than doubled in urban neighborhoods in tidewater Virginia since 1993. Photo by Bryan Watts.

Over the past 30 years, urban herons have held their own in Virginia. The population of yellow-crowned night herons has more than doubled over this time as pine trees in many neighborhoods have matured and now provide nesting substrates close to more marsh patches. Although the number of great egret colonies has declined and colonies are associated with fewer estuaries, the overall number of pairs has declined by only 20%. The number of known green heron pairs has declined by more than 40%, but this species is particularly difficult to survey and monitor.

Great egret carries a stick back to the colony in Hampton Virginia to build nest. Although the number of both colonies and pairs has declined within urban neighborhoods since 1993, great egrets remain a visible component of tidewater estuaries. Photo by Bryan Watts.

Driving through the dozens of neighborhoods during the spring of 2018 has been like traveling down memory lane with the ghosts of herons past perched on many corners. Many of the nesting areas from the past are no longer being used. Since the 1980s, we have lost nine great egret colonies, some of which had been known for more than 50 years. Many of these had occurred on vacant lots that are now developed. Others were nesting over houses leading to the removal of all nest trees. Unwanted, the birds have been bounced from neighborhood to neighborhood with the end result that colonies are now restricted to fewer estuaries. For unknown reasons, yellow-crowned night herons prefer to build their nests over man-made structures including roofs, decks, driveways and cars. This behavior places the birds in direct conflict with homeowners, often resulting in owners removing trees or limbs to prevent nesting. Green herons fly under the radar and virtually all homeowners that host them never know they are present.

Adult yellow-crowned night heron preens on the edge of a nest as the brood waits for the second adult to return with dinner. Photo by Bryan Watts.

House in Portsmouth, Virginia with a colony of 259 great egret nests overhead. The yard is full of dead chicks, dropped fish and droppings which is why they are not welcome in neighborhoods. The house is currently for sale. Photo by Bryan Watts.

Despite all of the opposition of homeowners to their nesting, herons have been resilient and have found ways of persisting. Over the past 30 years, homeowners have come and gone. Many people who removed nest limbs or used other approaches to prevent nesting have died or moved away. They have passed through neighborhoods like the summer rain. But the herons still return each spring, building their nests, raising their young and foraging in the rich estuaries that are their homes too.

Data from CCB.