The fish factory

Eagle productivity continues slide

July 16, 2018

Urban herons hold their own

July 17, 2018By Bryan Watts | bdwatt@wm.edu | (757) 221-2247

July 16, 2018

The brown pelican and double-crested cormorant nesting colony on South Point Marsh is like a shape shifter where fish are harvested, consumed and magically converted to bird flesh. Located within an old marsh pasture on the south end of Smith Island, the colony is strategically positioned within the heart of the Bay and is one in a series of seabird colonies that stretch from Tangier Island north to Poplar Island. But South Point stands high above all of the others. In mid-July, when the metabolic engine revs up to its highest pitch, the colony is estimated to consume 4,900 kilograms (10,800 pounds) of forage fish per day, including staples like menhaden, bay anchovy and silversides. During the course of the season, the colony is estimated to consume 950 metric tons of fish. Many questions remain about the details of how the colony interacts with the various fisheries.

Adam Duerr, Steve Mcininch and Dave Harper record fish species found in nests of the South Point Marsh colony. More diet work is needed to stratify the fish demand according to fish species to assess possible relationships to stocks. Photo by Bryan Watts.

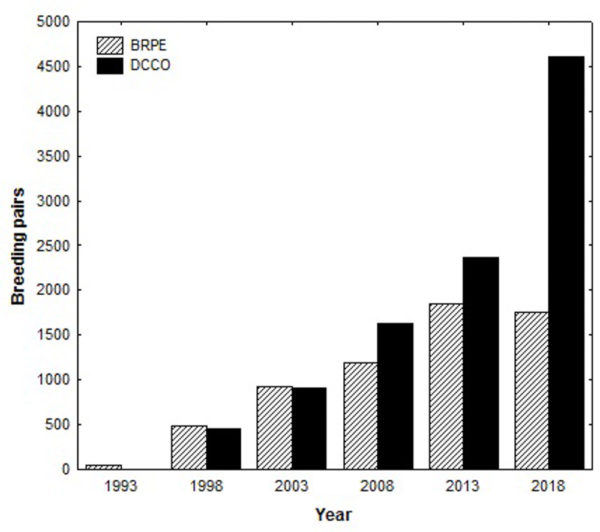

Changes in brown pelican and double-crested cormorant numbers within the South Point Marsh colony over time. Data from CCB.

The development of South Point Marsh into one of the great natural fish factories in the Chesapeake has happened over a short period of time. In June of 1993, Gary Costanza was working black ducks on the Bay islands when Mitchell Byrd and Bryan Watts hitched a ride out to Fishbone Island to check on a tern colony and then up to South Point to survey the emerging colony that they had seen from the air. The tide was ebbing fast, threatening to strand the boat for several hours on the expansive flats around Cheeseman Island as Gary put them off on the beach. They had only minutes to scramble up over the low dunes and work through the colony. Fifty-three pelican nests were scattered through the vegetation. In a small cluster just on the crest of the dunes was a group of six cormorant nests with fresh eggs.

Southern corner of the South Point Marsh colony. The colony now stretches nearly 1 km to the north. Photo by Bryan Watts.

Colony-wide metabolic demand peaks in July when the young are large but still growing. Photo by Bryan Watts.

As part of the state-wide colonial waterbird survey, CCB has had the opportunity to monitor the South Point colony over the years. The most recent count conducted on 31 May, 2018 found 1,753 brown pelican nests and 4,606 double-crested cormorant nests. After a dramatic increase through the 1990s and early 2000s, pelicans appear to have stabilized and come off of their peak of 1,857 pairs counted in 2013. Cormorants continue to demonstrate explosive growth, nearly doubling since 2013 and now dominating the colony. Collectively the breeding pairs represent the largest seabird colony within the mid-Atlantic region.

Two young brown pelicans in the nest with their next meal including Bay anchovy and menhaden. Photo by Bryan Watts.

Threadfin shad from a cormorant nest within the South Point Marsh colony. Photo by Bryan Watts.

During the peak season, the South Point colony is a beehive of activity with fish-laden adults arriving from all directions. The movement and sounds of adults and young rival that of Times Square during rush hour. But the smells of addled eggs, dead young, rotting fish and guano are more like the rising stench of a landfill on a hot summer day. The specific relationship between the colony and the fisheries it depends on is still poorly understood. What is the size and shape of the net the colony casts on the Bay? During the summer of 1999, Bryan Watts, Dana Bradshaw and Marian Watts made observations of the colony for more than a month. Pelicans rose out of the colony on thermals nearly out of sight overhead and moved off great distances to forage. Pelicans are now observed up the Potomac River as far as Colonial Beach during the summer, suggesting that the pelicans are harvesting fish from a large portion of the Bay. But details on their foraging behavior and what impact the seabirds may be having on the various fisheries remain to be explored.