Gender Divide in Bald Eagles

Virginia Peregrines have Mixed Year in 2017

January 8, 2018

Flying to Mecca

March 30, 2018By Bryan Watts | bdwatt@wm.edu | (757) 221-2247

January 8, 2018

Unlike many familiar bird species, male and female bald eagles have identical plumage making them difficult to distinguish in the field, but they are not the same. In the hand, females have distinctly larger feet and this character alone may be used successfully to separate the sexes. Females are 30% heavier than males with a nearly 20% longer tarsus (lower leg bone). Females also have longer wings and deeper bills than males. When standing together, males and females of a mated pair are nearly always easy to distinguish. However, geographic variation confounds separation on the basis of size alone when birds are alone or in mixed groups.

A pair of eagles on breeding territory in Norfolk, VA. The male (lft) is noticeably thinner and smaller than the female (rt). Photo by Duane Noblick.

Beyond the measurements, males and females cut a different line across the sky. Differences in weight result in subtle differences in the proportions of body to wings that with experience may be observed in flight. It is like watching a quarter horse and a draft horse running across a field. The differences in weight and build influence movement. Female eagles express a more labored flight style. Watch closely for these differences the next time you see a group of eagles in active flight.

Bryan Watts holds a fourth-year female (lft) and third-year male (rt) eagle in the Chesapeake Bay to illustrate differences in foot size between the sexes. Male feet are dainty compared to females. Photo by Bart Paxton.

During the breeding season there is a division of labor between the sexes that extends to incubation. Females have a much larger brood patch, making them more suited to incubate clutches and brood small young, particularly during poor weather. Females cover more of the incubation duties and incubate when they choose. In effect, males fill in for the female when she wants to be relieved. This dynamic is readily apparent when observing shift changes. If the male returns to the nest to relieve the female without being called she may or may not accommodate the male regardless of how vigorously he attempts to replace her. By comparison, if the female returns to the nest she will supplant the male regardless of how long he has been incubating.

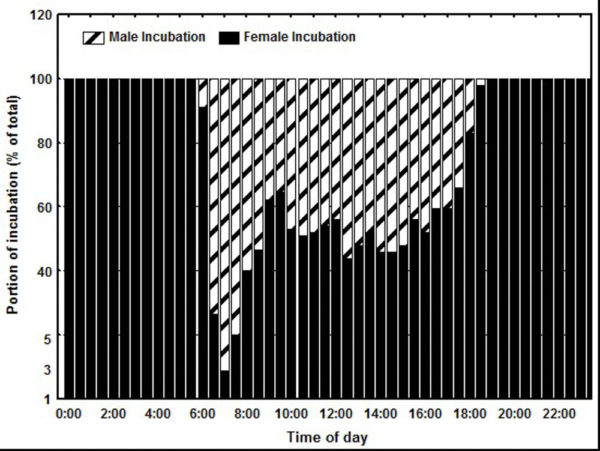

Average division of incubation duties between male and female bald eagles in the Chesapeake Bay. Females do the lion’s share of the incubation mostly because they take the night shift. Composite data from seven eagle nests monitored with video cameras. Data from CCB.

Although patterns may vary between pairs, for nests within the Chesapeake Bay, females observed on video accounted for 73% of the incubation duties on average. The gender disparity was driven primarily by the female taking the night shift. In all cases recorded (>150), the female covered incubation for the night. Night shifts averaged 13 hours and 20 minutes, or more than half of the 24-hour cycle. During the daylight hours between 6:00 AM and 4:00 PM, the pair split incubation duties relatively evenly.

A male bald eagle (rt) along the James River waits patiently to relieve the female of her incubation duties after the long night shift. Photo by Bryan Watts.

One of the more interesting aspects of the team effort is that the length of the night shift imposes a basic structure on the daily pattern of incubation. The most predictable shift change occurs around dawn after the long shift performed by the female. The male is punctual in relieving the female and often performs his longest shift of the day. Covering the early morning shift allows the female to leave the nest and take care of self-maintenance activities such as feeding and preening. When she returns, the female typically performs her longest shift of the daylight sequence. The afternoon is the most dynamic period within the 24-hour cycle, with multiple exchanges and short shifts. The day typically concludes with the male performing his shortest shift of the day just before the female settles in for the long night shift.