The leaving ecology of whimbrel

Grace Visits Norfolk Returns to Surry County 20170911

September 11, 2017

Hope survives

September 13, 2017By Bryan Watts | bdwatt@wm.edu | (757) 221-2247

September 12, 2017

We have spent years standing on Box Tree Dock listening for their rallying calls through the chorus of laughing gulls and clapper rails and looking south for them to rise over the horizon of marsh. For many whimbrels, this is the last time they will touch the ground until they land on their Arctic breeding territories. As flock after flock have passed overhead, we have logged their numbers in the hope of better understanding their “ecology of leaving” and how this event figures into their annual cycle. The Delmarva Peninsula in Virginia represents a refueling site for whimbrels moving from winter areas in Brazil to Arctic breeding grounds. What time of the day do most of the birds form up flocks and take off? What is the distribution of flock sizes that leave? What is the spring departure schedule? These questions provide a glimpse into the many factors that have shaped their migration. Like all ecological projects, it has been a journey of discovery. At the close of each day we have hung onto each bit of information trying to make out the grander view.

A flock of whimbrel passes over Box Tree Dock on their way to Arctic breeding grounds. Photo by Alex Lamoreaux.

Alex Wilke scans south along the horizon for whimbrel flocks moving north. Photo by Bryan Watts.

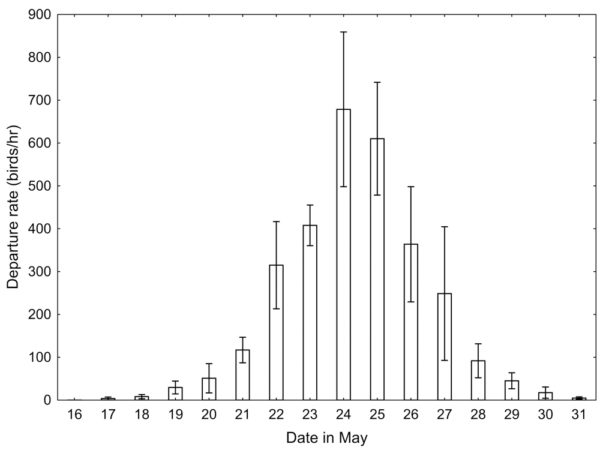

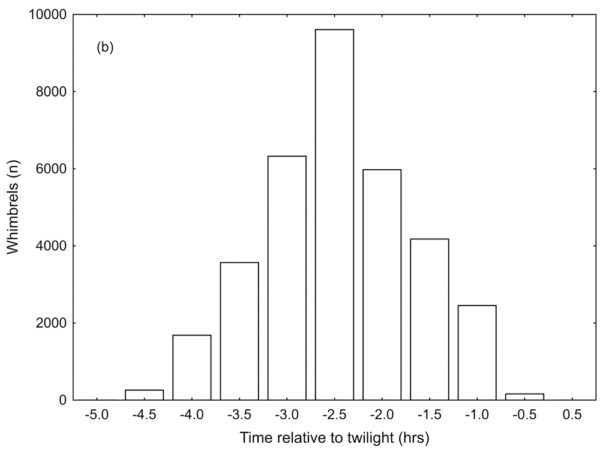

Recently, we have compiled WhimbrelWatch data collected between 2009 and 2014 and published a paper entitled Departure patterns of Whimbrels using a terminal spring staging area in the journal Wader Study. During the six-year period, we recorded 727 whimbrel flocks leaving the lower Delmarva that contained 39,720 birds. Amazingly, the peak leaving date varied only three days (23 to 25 May) across six years. During these peak leaving times, flocks were recorded every six minutes on average and the leaving rate exceeded 600 birds per hour. Departures peaked approximately 2.5 hours before civil twilight with 82% of individuals leaving within the two-hour period between 1.5 and 3.5 hours before twilight. Flock size ranged as high as 270 individuals and average flock size varied throughout the afternoon, with the largest flocks leaving during the onset of exodus. The distribution of departing flock sizes approximated a negative exponential as smaller flocks were more common. The result of this pattern is that although 50% of all flocks recorded contained less than 35 individuals, 50% of all individuals occurred in flocks that contained 80 individuals or more.

Seasonal pattern of whimbrels leaving the lower Delmarva Peninsula (2009-2014) for breeding grounds in the Arctic. Peak leaving date was highly consistent between years. Data from CCB.

Daily pattern of whimbrels leaving the lower Delmarva Peninsula (2009-2014) for breeding grounds in the Arctic. Why birds leave before dusk is unknown but may provide some initial navigational benefits. Data from CCB.

Group travel in shorebirds is believed to provide benefits to flock members such as collective navigation and energetic savings related to flock aerodynamics. These possible benefits for flocking have not been tested in whimbrel. The highly synchronous and consistent departure pattern may help to facilitate synchronous arrival on the breeding grounds and reinforce mate fidelity. Nesting season in the high Arctic is very short, placing a premium on preparations that allow birds to take advantage of breeding opportunities as they arise.

Tom Pelton (left) from National Public Radio records whimbrels calling as they pass over Box Tree Dock while Barry Truitt (right) discusses some of the fine points of whimbrel migration. Photo by Bryan Watts.

Over the years, Box Tree Dock has become a window on whimbrel migration and a gathering place for many offering educational opportunities for school groups and a venue for birding groups and individuals. We thank all of those observers who have contributed to the success of WhimbrelWatch.