National Park Service and CCB continue to assess exposure of eagle nestlings to contaminants

Crossover Knots

July 12, 2017

Grace Remains at TRS July 16, 2017

July 17, 2017By Bryan Watts | bdwatt@wm.edu | (757) 221-2247

July 13, 2017

The National Park Service (NPS) is the keeper of our most precious crowned jewels. It manages the places that hold the essence of our history, culture, and natural wonders, the spectacles that we describe with pride to visitors that travel from other nations, and the inspirational vistas that we all run to for solitude and contemplation. In addition to their cultural importance, this portfolio of lands is also the infrastructure that supports our most imperiled wildlife. We, as a people, entrust all of these most valuable possessions to the staff of the National Park Service – a charge that they accept with pride and commitment.

Bart Paxton measures bill depth on a young eaglet fitted with a hood. Photo by Bryan Watts.

National parks have been instrumental in the recovery and maintenance of many threatened species and often support the best remaining examples of intact ecosystems. They have played a critical role in the recovery of bald eagles. Within the Chesapeake Bay, colonization rates and subsequent breeding densities of eagles on park lands have far outpaced those on private lands. Parks now support a significant number of breeding pairs. Although these parks are managed with a mandate to provide habitat for existing territories, breeding pairs should not be considered secure due to the continuing risk of exposure to environmental contaminants emanating from external sources. Park Service biologists understand that managing wildlife populations often requires mitigating risks coming from outside park boundaries, and that park properties often represent some of the best opportunities to monitor the health of larger systems that contain them.

Marie Pitts and Bart Paxton process a bald eagle nestling on the Potomac River as Seth Berry records data. Photo by Bryan Watts.

Elaine Lesley from the National Park Service places blood samples in a cooler as Bart Paxton and Marie Pitts hold an eaglet on the examining table and Erin Chapman looks on. Photo by Bryan Watts.

For a second breeding season, CCB and NPS biologists collected blood samples from nestling bald eagles from park lands within the Chesapeake Bay to monitor for contaminant exposure. The 2017 effort focused on park lands along the Potomac River, including The National Capital Region. Blood and other tissues were collected from 11 eagle broods. The ongoing study is a collaborative effort with eagle biologists from the Great Lakes and will compare contaminant exposure experienced by eagle broods in the Chesapeake Bay to those reared on NPS lands within the Great Lakes Region.

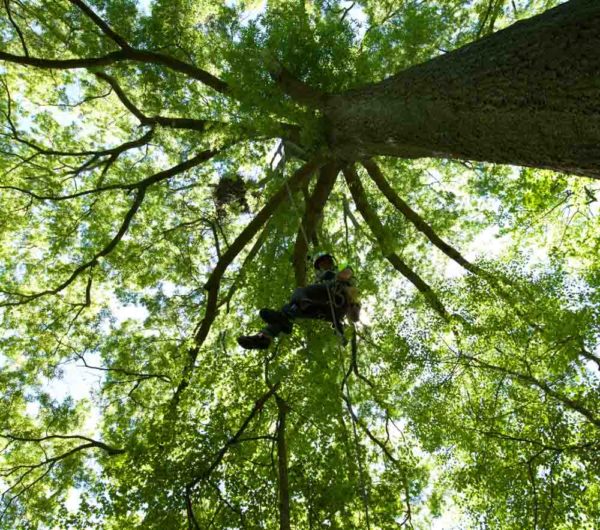

Steve Connally repels from an eagle nest in the crown of a huge oak along the Potomac River. Nest trees were climbed, broods were lowered to the ground, processed and returned to the nest. Photo by Bryan Watts.