Plovers Navigate the Dangers of Hurricane Matthew

Grace Returns to Virginia Beach Jan 8, 2017

January 9, 2017Tracking eagles in 3D

January 11, 2017

For over a century, people have wondered what exactly happens when birds encounter hurricanes. Even into recent decades, the behaviors of birds in hurricanes were purely speculative, or based on few direct observations. Resident breeding birds along the Atlantic Coast have adapted to periodic hurricane events, though even localized storm damage can impact populations of some bird species. The impact of large storms on barrier island or beach systems isn’t always negative, and some birds (piping and snowy plovers, for instance) have adapted to nesting in the overwash areas created by cyclones, nor’easters, and other large storm events. Migratory birds have a different relationship with hurricanes, with the probability of encountering a storm overlapping with only a small window of time of their annual cycle. Though the odds are unlikely, the chance encounters have drastic implications for smaller land birds that face a storm over the open ocean, and many passerines likely perish within the winds of large tropical systems. Pelagic birds can ride the winds and find themselves inland, hundreds or even thousands of miles away from typical open-ocean locations. Some birds find themselves “stuck” in the center of storms unable to break through the wall of wind to reach safety.

Satellite tagged black-bellied plover being released on breeding grounds in the High Arctic. Photo by Fletcher Smith.

Until recent years, it was generally an accepted theory that most birds that migrated into large hurricanes over the open Atlantic perished. Through the amazing remote tracking technologies available to scientists, we now know that at least some types of birds are able to navigate directly through these storms and beyond. Remotely tracking a migratory bird into a Category 3 hurricane and seeing the bird safely make it through the other side of the storm has the power to captivate anyone.

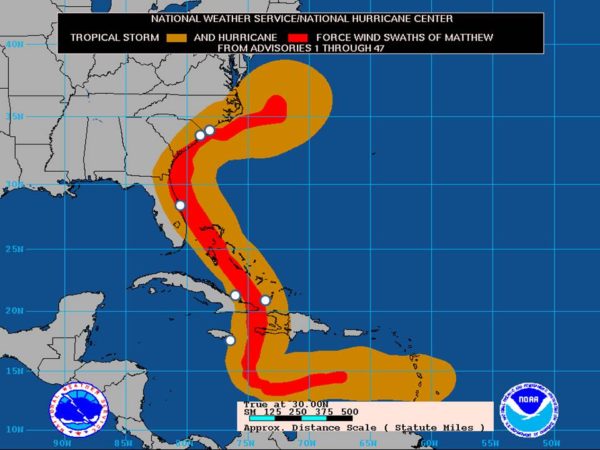

With all of this in mind, we watched in near-real time as six black-bellied plovers settled into their migratory stopover sites or wintering locations in Jamaica, Cuba, Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina, just as Hurricane Matthew picked up intensity and made towards the region in early October 2016. All of these plovers were tagged in the High Arctic breeding grounds in 2015 and 2016.

Location of satellite tagged black-bellied plovers (white dots) during Hurricane Matthew. Image courtesy of NOAA National Weather Service/National Hurricane Center.

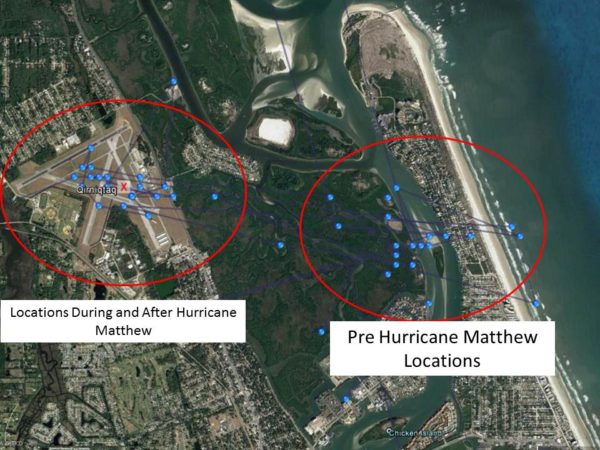

Amazingly, all of these birds made it through the storm, and we were able to look at the strategies the birds used to avoid the worst of the storms as the hurricane strafed the region. When we zoom in on the plover in Florida (Qirniqtaq, image below), we can see the bird move from the marshes and beaches of New Smyrna to the nearby airport, a likely refuge from the storm surge that Matthew brought with the winds. This plover appears to have set up shop in the airport now and may continue there through the winter.

Wintering locations of Qirniqtaq, with the marsh and beach locations recorded prior to the storm, and the airport locations recorded during and after the storm. Data from CCB.

The technological breakthroughs in tracking birds have given the scientific community the ability to see behaviors and migrations with incredible detail. With each breakthrough in the reduction of size and weight of transmitters, more bird species become available to track. The deployment of transmitters on black-bellied plovers is a collaborative effort between Canadian Wildlife Service (CWS) and The Center for Conservation Biology, and was initiated by CWS in 2014. The goal of the tracking study is to understand the connectivity of arctic nesting shorebirds to stopover sites and wintering grounds. Understanding the linkages of the plovers and other shorebirds is critical to the conservation of these birds along the flyway. The tracking of the plovers is an ongoing project and they can be followed at Wildlifetracking.org.

Written by Fletcher Smith | fmsmit@wm.edu | (757) 221-1617

January 10, 2017