Citizen scientists work to fill the nightjar information gap

Grace at Bethel Landfill Hampton Sept 25 2016

September 26, 2016Mapping bald eagle movement corridors in the Northeast

September 27, 2016

Whip-poor-wills and other nightjars are part of our collective past times. Before television and social media filled many of our evening schedules, the simple summer pleasure of sitting out on the front porch to watch the sun slip behind the tree line and to hear the night sounds rise from the darkness was a frequent experience. A highlight of the evening was to hear the distinctive calls of whip-poor-wills echoing back and forth across the landscape advertising their territories. Throughout the continent we hear less of them now. It is not just that we are listening less, but that fewer birds are there to perform their distinctive songs.

Chuck-will’s widow on nest in Virginia. Photo by Bart Paxton.

Over the past four decades there has been a growing concern within the conservation community that some species of nightjars are experiencing rapid declines over much of their breeding ranges. Their ecology is poorly understood. Because national monitoring programs are conducted during daylight hours and nightjars primarily call after dark, we have had very little information to assess changes in distribution and abundance.

Typical pine savannah habitat used by chuck-will’s widow in the southeastern United States. The fire-maintained, open, park-like habitat seems to be preferred. Photo by Bryan Watts.

Concerned citizens are the hearts and hands of the conservation movement. The history of conservation as a cause and as a science emerged from regular people who had an outsized passion and concern for the future of our world. Even with the increasing sophistication of science as a profession, there is no substitute for the many eyes of the public. Some of the most pressing questions that confront us today are so large in scope that the fieldwork needed to address them is simply not possible without citizen scientists.

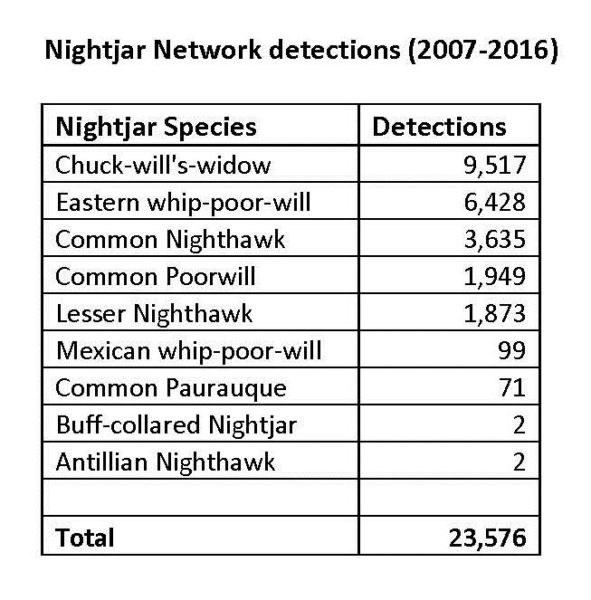

In 2007, The Center for Conservation Biology called on citizen scientists to help fill the information gap with nightjars by initiating the Nightjar Survey Network. The response has been both gratifying and overwhelming. An army of birdwatchers, agency biologists, and nightjar lovers have volunteered during the wee hours of the night to conduct standardized surveys of routes across North America. The effort has resulted in the most comprehensive database to date on the group.

A total of more than 23,000 nightjars of nine species have been recorded during surveys. We would like to express our gratitude to the many observers across the continent who have given of their time and expertise to make this effort possible. Over the next year, CCB biologists will begin to explore the database for spatial and temporal patterns that will help with future nightjar management. Moving forward, we hope to expand the volunteer base and survey network into additional areas that have received little coverage.

Written by Bryan Watts | bdwatt@wm.edu | (757) 221-2247

September 26, 2016