Fruit availability and consumer demand within a migration bottleneck

Grace on James River at Brandon Point Sept 16, 2016

September 19, 2016

Grace at Bethel Landfill Hampton Sept 25 2016

September 26, 2016

There are few things in life that match the electricity of standing within a major fall staging area during a morning fall-out event. In the pre-dawn hours the sky is full of sound. As the sun begins to rise you can see the birds appearing in mid-air by the thousands like raindrops falling from nowhere. The ground, shrubs, and trees fill and wake with the energy of birds. Like Niagara Falls or the spring drumming of a ruffed grouse, it is a natural spectacle to be experienced in person with all of your senses turned up to high. And like many spectacles, these events are followed by the faithful who come out whenever a good cold front is expected to deliver a great show of birds. Wise Point, situated on the tip of the Lower Delmarva Peninsula, is one of the best locations in eastern North America to experience the massive waves of passerines that flow down the Western Atlantic Flyway. Like a sea wall, the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay stops these waves and deposits birds on this narrow peninsula. Almost immediately upon settling out the birds begin to scour through the vegetation for food to replenish the fuel that they have burned through the night. Fruit is an essential component of habitat quality for fall migrants.

Selected fruit species used during the fall by passerine migrants on the Lower Delmarva Peninsula. Included (top to bottom) are fox grapes, bayberry, autumn olive, and devil’s walkingstick. Photo by Bart Paxton.

Have you ever wondered what types of fruit migrant passerines eat during migration? Or more importantly, have you ever wondered how we might actively improve the landscape to support these birds during their migration? During the fall of 2014, The Center for Conservation Biology, along with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, conducted a study to examine the availability of fruit and which fruits were important to passerine migrants on the lower Delmarva Peninsula (download report). CCB technicians Sarah Rosche and Arianne Millet performed more than 2,000 vegetation assays to evaluate the composition and density of fruiting plants and the density of fruit production within selected forest and shrub patches. They monitored nearly 500 fruiting branches of 12 species that supported more than 24,000 fruits weekly during the study period to assess patterns in fruit ripening. These branches were included in an exclusion experiment (covered versus exposed) that we used to evaluate rates of fruit loss, fruit consumption, and fruit preference.

Sarah Rosche counts bayberry fruits to be used to calculate consumption rate. Photo by Bart Paxton.

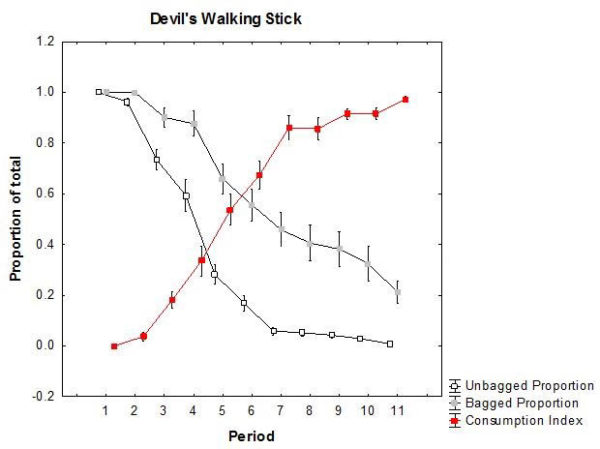

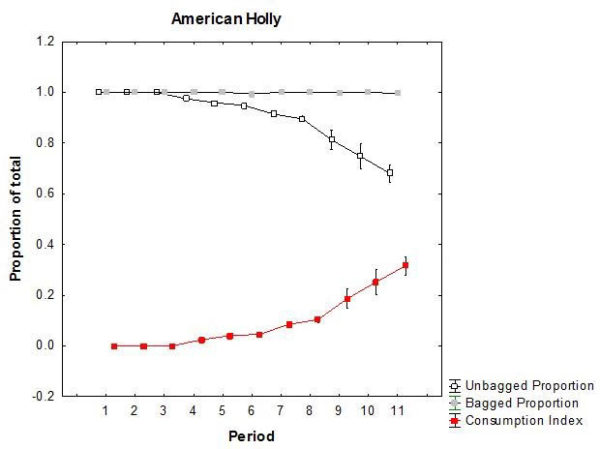

The seasonal schedule of fruit ripening varied dramatically between plant species such that the availability of ripe fruits changed during the migration period. Some of the fruits, including American holly and hackberry, matured too late to have relevance for most migrants. Based on the exclusion experiment, an index of consumption varied significantly between fruit species. Sassafras, devil’s walkingstick, fox grapes, and autumn olive had consumption rates of more than 15% per week compared to hackberry, beautyberry, and bayberry that were less than 5% per week. Fruit species fall into three preference categories including high demand, medium demand, and low demand. Migrants stripped virtually 100% of fruits in the high demand category during the height of the migration season.

Devil’s walkingstick sample showing fruit stripped from exposed branches. Photo by Bart Paxton.

Mature forest and shrub patches differ dramatically with respect to the composition of the fruiting plant community, plant density, fruit density, and the extent to which they support preferred fruit species. Although fruit density within shrub habitat was more than ten-fold higher than forest patches, 95% of the crop is of low demand or is produced by an exotic invasive species. Shrub patches should be managed to broaden out the fruiting plant community to include preferred fruit species. Management prescriptions should be developed that drive the footprint of the less desirable plants down and expand the more desirable elements.

Devil’s walkingstick was a preferred fruit by migrants on the Lower Delmarva Peninsula. Covered and exposed branches diverged over the season and the consumption index ultimately rose to 1. Data from The Center for Conserv

Although an important winter fruit, American holly ripens late in the fall and was not a preferred fruit by migrants. Very little of the standing stock was used during the migratory period. Data from The Center for Conserv

This field study follows a previous study by CCB that examined metabolic demand by migrants stopping over on the Lower Delmarva Peninsula and conservation limits (download report). These projects have been completed to inform land management within this important staging site.

Written by Bryan Watts | bdwatt@wm.edu | (757) 221-2247

September 19, 2016