Breeding peregrines consolidate along the mid-Atlantic coast

Graces Returns to Virginia Jan 7 2016

January 11, 2016Black-bellied Plovers Tracked to Wintering Grounds

January 11, 2016

Historically, an estimated population of 350 pairs of peregrine falcons nested throughout the Appalachians and along the coast of New England. By the early 1960s, this entire population had been lost to contaminants and other factors. An eastern recovery team was appointed in 1975, and in the absence of any residual breeding stock the team would decide on a bold plan – they would establish a captive breeding program and re-establish the wild population through releases. Cornell University stood up a captive-breeding program in short order with enough capacity to fuel an aggressive release program. Experimental releases included both natural cliff sites and artificial towers constructed in coastal marshes. However, early results quickly focused release efforts on coastal towers. Twenty coastal towers were established during the early release phase from Virginia north through New Jersey.

Everyone pitches in to place the peregrine hack box on the tower constructed within the Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge in Virginia in 1979. This tower would later be the site of first breeding in the state in 1982. Photo by CCB.

Between 1975 and 1985, 307 captive-reared peregrine falcons of mixed heritage were released within the mid-Atlantic Coastal Plain, a physiographic region with no historical breeding population, as part of the eastern peregrine recovery program. Modern breeding records would be recorded in 1980 for New Jersey, 1982 for Virginia, 1983 for Maryland, and 1987 for Delaware. The history of this unusual population is the focus of a recent paper published by CCB and colleagues within the region entitled, “Establishment and growth of the peregrine falcon breeding population within the mid-Atlantic Coastal Plain.”

Doug Davis (left) and Hans Gabler (right) place the first captive-reared peregrines in the hack box on Cobb Island in 1978. The Cobb Island tower continues to support a breeding pair today. Photo by CCB.

The coastal population has progressed through two stages, including an establishment phase (1979-1985) and a consolidation phase (1986 to present). The establishment phase was fueled by the release of captive-reared falcons and exhibited an average doubling time of only 1.3 years. This phase was characterized by rapid colonization but relatively low productivity. Following the conclusion of releases, population growth declined dramatically to an average doubling time of 23.4 years but productivity increased from 1.18 young per pair to 1.87 young per pair. The population had become self-sustaining and was growing on its own. This population has continued to expand and the mid-Atlantic Coastal Plain now supports more than 70 breeding pairs.

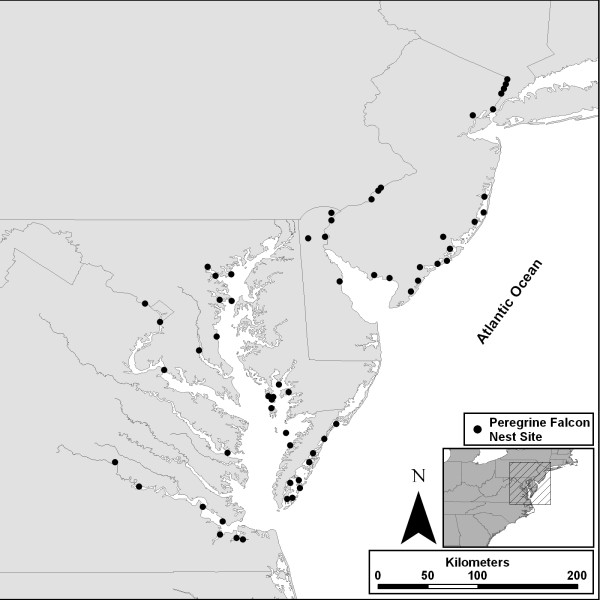

Map of occupied peregrine falcon breeding territories throughout the mid-Atlantic Coastal Plain in 2007. Data from CCB.

In 2015, Virginia supported 26 breeding pairs of peregrine falcons. Twenty-three of these pairs were in the Coastal Plain, with an additional pair in the Piedmont and two pairs in the mountains. New breeding territories were documented on a smoke stack within a power station and on a building within an urban area. The population achieved an overall success rate of 80.7% and produced 56 young to banding age. The reproductive rate was 2.15 young/occupied territory which is above the level required for population maintenance.

Adult female that established a new breeding territory on a Virginia smoke stack in 2015. This bird was hatched on the Tuckahoe River in New Jersey. Photo by LIbby Mojica.

Doug Smith, Kip Holloway, and Tom Mansfield from the Virginia Department of Transportation move a nest tray on the I-64 high-rise bridge to facilitate management. VDOT has been a great partner in the recovery of peregrines in Virginia. Photo by LIbby Mojica.

Project Partners: The success of the peregrine management program in Virginia is the clear result of the large community of agencies and individuals that have become committed to the population. The community effort is showing results. Partners in the effort include the Virginia Department of Game & Inland Fisheries, Virginia Department of Transportation, Dominion, The Nature Conservancy, NASA, U.S. Department of Defense, U.S. Coast Guard, National Park Service, U.S. Forest Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Virginia Tech, and The Center for Conservation Biology.

Written by Bryan Watts | bdwatt@wm.edu | (757) 221-2247

January 11, 2016