High latitude satellite tracking of migratory plovers

Biologists prepare for historic woodpecker move

September 29, 2015

Grace Stays at Brandon Point Sept 25 2015

October 4, 2015

During the Arctic summer at Polar Bear Pass National Wildlife Area, located on Bathurst Island in Nunavut, Canada, fierce sub-zero winter conditions gradually give way to the warmth of 24/7 daylight, melting snow, and filling ephemeral pools and ponds that provide breeding grounds for countless insects. Herds of Musk Oxen and Peary Caribou shake off their winter coats and begin congregating in the marshy tundra to eat the newly abundant grasses and sedges. Lemmings and their predators, including Snowy Owl, Arctic Fox, and Jaegers, begin their annual survival race. This is the time period when shorebirds migrate to the Arctic latitudes to begin their breeding season. The shorebirds are drawn to the high latitudes to sync their egg hatching with the abundant insect life of the Arctic summer.

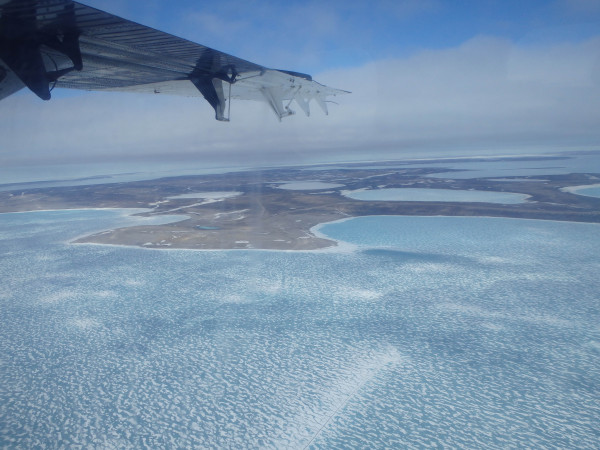

Aerial view of the Archipelago waters before ice break-up in late June 2015. Photo by Fletcher Smith.

Herd of Musk Oxen gather on an esker just above Polar Bear Pass National Wildlife Area. Photo by Fletcher Smith.

Peary Caribou, an endangered subspecies of high Arctic caribou, graze near the study area. Photo by Fletcher Smith.

The shorebird team, consisting of Canadian Wildlife Service (CWS) biologists, technicians, and myself, arrive in late June just after the snow melts. We are in luck, because in years past the CWS staff has been greeted by deep snow and blizzards in early July. We enjoy mild Arctic weather throughout the season, with temperatures above freezing during the entire expedition and countless sunny days. The only drawback to such great weather is the temporally advanced state of shorebird nesting, with many species already incubating complete clutches of eggs when we arrive. Ideally the field season would commence during the early stages of nesting and incubation, but predicting the snow melt date is incredibly difficult to do year to year at these high latitudes.

The 2015 shorebird crew poses in front of a hoodoo. The team consisted of Paul Woodard, Beth MacDonald, Julie Belliveau, and Fletcher Smith. Photo by Fletcher Smith.

Home sweet home during the 2015 season. This cabin was built in the late 1960s but has stood the test of time. Renovations by CWS staff during the season will ensure another half century or more of use by future researchers. Photo by Lisa Pirie/CWS.

Daily activities include monitoring study plots for breeding shorebirds using both Arctic Shorebird Demographic Network (ASDN) and the Program for Regional and International Shorebird Monitoring (PRISM) protocols. Data collected across the Arctic is compiled and important parameters such as breeding success, adult survivorship, and breeding densities are used to model the populations of shorebirds across a vast geographic region. Nests are found using a variety of behavioral clues and by walking nearby to flush birds off of nests in likely breeding habitat. Nest success is tracked using a form of the Mayfield method. Mayfield himself spent several summers at Polar Bear Pass studying the breeding ecology of Red Phalaropes. We apply a unique color combination and/or alpha-numeric flag on virtually all captured shorebirds. On select shorebirds, we apply VHF radio “nanotags” in an effort to track southbound migration through an array of VHF receivers positioned along the Atlantic Coast of Canada and the United States.

Sanderling with alpha-numeric leg flag “A18.” This bird was resighted in Delaware Bay during the fall migration. This bird was also tagged with a VHF radio transmitter and was likely detected migrating through the array of receivers in Eastern Canada and the U.S. Photo by Fletcher Smith.

Eyrie of a N. Rough-legged Hawk pair. This eyrie was first discovered by H. F. Mayfield et al. in the early 1970s. We were able to find this eyrie roughly 15km north of camp based on descriptions of the site left in field notes in the cabin. Photo by Fletcher Smith.

The main objective on this expedition is to deploy six 5-gram satellite transmitters on Black-bellied Plovers nesting within the study site. Very little is known about the annual life cycle of shorebirds, and as tracking devices become smaller more species find themselves as candidates for satellite tracking, allowing researchers a remote glimpse into their migration routes and life cycles from afar. Black-bellies fit the profile well for tracking – they are fairly large compared to the small transmitters, they have the proper body structure to hold a harness, and they are abundant and easy to catch at the study site. Plovers are trapped on nests and the transmitters are attached during the incubation cycle.

Black-bellied Plover with satellite transmitter in her territory. Photo by Fletcher Smith.

The tracking of Black-bellied Plovers is a collaborative effort between Canadian Wildlife Service and The Center for Conservation Biology and was initiated by CWS in 2014. Logistical support for the Bathurst Island field expedition was provided by the Polar Continental Shelf Program in Resolute, Nunavut. The tracking of the Plovers is an ongoing project and the birds can be followed at Seaturtle.org.

Purple Sandpiper in breeding plumage, image taken near Resolute, Nunavut. Purple Sandpipers have the northern most winter range limit of any of the high Arctic breeding shorebirds. Photo by Fletcher Smith.

Snow Bunting. These passerines were a common breeder on the limestone and shale cliffs of Bathurst Island. Photo by Fletcher Smith.

Snowy Owl hunting on the ridge of an esker near camp. Many Snowy Owls were observed during the 2015 field season, suggesting a high number of their lemming prey in the area as well. Photo by Fletcher Smith.

Polar Bear lumbering through Polar Bear Pass National Wildlife Area. These bears typically reside near the coast in summer waiting for ice to form to resume hunting. This bear was an exception and was spotted about 15km inland. Photo by Fletcher Smith.

Written by Fletcher Smith | fmsmit@wm.edu | (757) 221-1617

September 30, 2015