Sharing the story of Hope

Young eagles are more likely to eat junk food

September 24, 2015Biologists prepare for historic woodpecker move

September 29, 2015

We live in a contradictory time when we are both more connected across the planet by the internet but less connected to the natural world than during any other time in human history. One of the great challenges of the conservation community is to find ways of breaking through the constant clamor and engage people in real dialogue about how their daily decisions are relevant to the future of other species – to push pause long enough to contemplate how we may contribute to solutions.

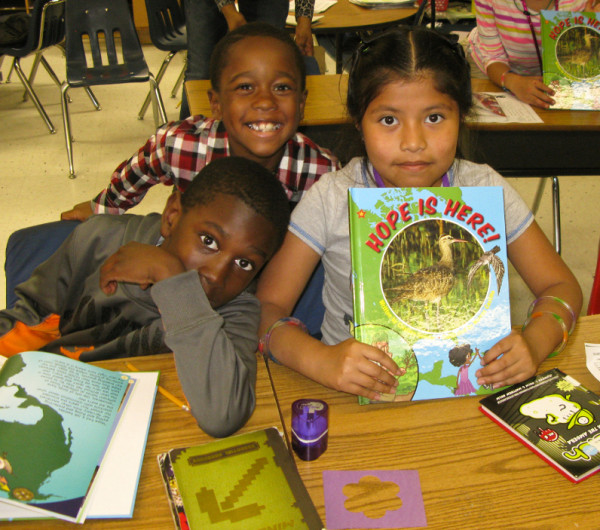

Pungoteague Elementary students display their new book about Hope the whimbrel and her migratory adventures. Photo by Bryan Watts.

The Eastern Shore of Virginia plays a critical role in the life cycle of several species of migratory shorebirds that are experiencing rapid declines. Tens of thousands of shorebirds come to the Shore each spring to refuel on fiddler crabs, marine worms, and mussels before making a non-stop flight to high-arctic breeding grounds. Depending on the species, these birds winter from the Caribbean Basin all the way south to the tip of South America. The Eastern Shore is a critical link in a chain of sites that stretches throughout the entire Western Hemisphere. One significant milestone in protecting this chain is for citizens to recognize that local actions have an impact on the conservation of these wide-ranging species. Awareness of one’s role in the larger conservation puzzle is a first step toward global citizenship.

Broadwater Academy students prepare for a lesson about the importance of the Eastern Shore to migratory birds. Photo by Bryan Watts.

During the spring of 2015, The Center for Conservation Biology, in partnership with the Barrier Island Center and three primary schools on the Eastern Shore, initiated a pilot project to engage young students in learning about the importance of their local landscape to migratory birds. The simple focus was to raise the environmental consciousness of local children. Three themes were emphasized to classes including 1) the importance of the Eastern Shore to migratory birds, 2) the fact that migratory birds connected them to other important locations and cultures and 3) the fact that local decisions and actions made on the Eastern Shore were relevant to the future of these migratory birds.

Sally Dickinson (left) and Laura Vaughan (right) from the Barrier Island Center discuss whimbrel migration and the Eastern Shore with students from Pungoteague Elementary School. Photo by Bryan Watts.

The team visited three schools and worked with nine classes to discuss migration. Each visit started with a presentation about migration and ended with a discussion about Hope the whimbrel and a reading of the children’s book “Hope is here”. Hope was caught on Boxtree Creek on the Eastern Shore in the spring of 2009 and fitted with a satellite transmitter. She was tracked back and forth between her breeding grounds on the Mackenzie River in western Canada to her winter home on Great Pond on St. Croix. Between 2009 and 2012 she was tracked for more than 50,000 miles. She became a star to the school children on St. Croix and in 2012, well-known children’s author Cristina Kessler wrote a book titled “Hope is here”. Hope and the book have become vehicles for teaching children about migration, the conservation challenge, and the role that children can play. After the reading, each student was presented with their own copy of the book. This was made possible through the generosity of Jane Batten, a champion for educating children about the environment.

Bryan Watts with students from Broadwater Academy after they received their own copies of Hope is here.”

Following the school visits, it remains unclear who was most inspired by the experience – students or teachers. We were not prepared for the level of engagement, enthusiasm, and curiosity of the children. The quality of questions about migration ecology, the level of concern about populations in trouble, and the curiosity about other children and cultures elsewhere along the migratory route was hopeful. We thank the principals and teachers of Pungoteague Elementary, Broadwater Academy, and Kiptopeke Elementary for partnering on this effort. We hope that this will become an annual program in the future.

Written by Bryan Watts | bdwatt@wm.edu | (757) 221-2247

September 28, 2015