The Wanderers

Grace Makes Week-long Circuit Flight – Sept 19, 2015

September 21, 2015Young eagles are more likely to eat junk food

September 24, 2015

We know very little about the time between when birds leave their natal territories and when they settle on their winter grounds. Although the period is a black hole of information, it is believed to be a critical time packed with learning and exploration when birds become self-sufficient, prospect for future breeding locations and learn about their extended neighborhood. Because individuals disappear during this dispersal period, questions about their activities during these formative months have remained beyond our reach. The development of satellite tracking techniques has ushered in a new era of ecological inquiry and for the first time has allowed us to peak into the private lives of birds wherever they go.

A young peregrine falcon with solar-powered, satellite transmitter used to track movements during dispersal and beyond. Photo by Bryan Watts.

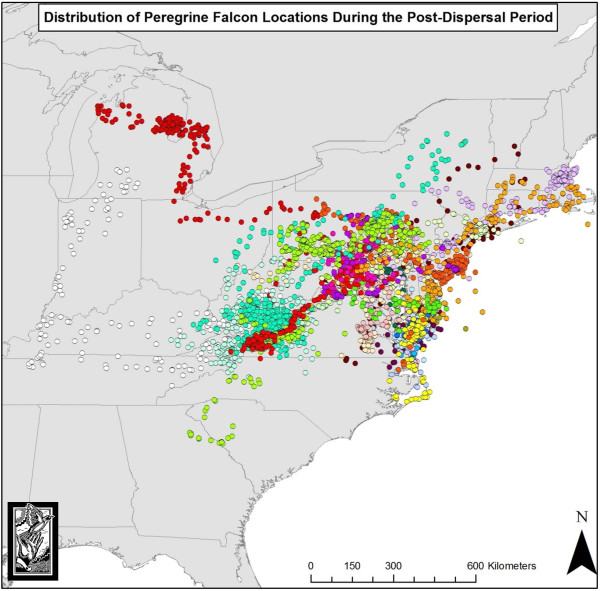

Over a decade beginning in 2001, CCB deployed satellite transmitters on 61 young peregrine falcons to answer several questions about migratory strategy, winter destinations, the process of establishing breeding territories, and the nature of the dispersal period. Transmitters delivered more than 66,000 usable locations on birds covering important periods of the annual cycle. The dispersal period was characterized by long movements and wide-ranging exploration. The length of this period averaged 48 days before birds initiated directional flights to winter territories. During this time, birds visited 23 states with activities concentrated along the Atlantic Coast and southern Appalachians. Inland movements were bounded by the Great Lakes to the north and the Mississippi River to the west. Birds showed a clear attraction to major metropolitan areas including Washington D.C., Baltimore, Pittsburg, Philadelphia, New York City, Boston, Cleveland, and Detroit.

Mitchell Byrd (standing), Bryan Watts (middle) and Shawn Padgett (right) attach a satellite transmitter to a peregrine falcon on the Eastern Shore of Virginia. Photo by Bart Paxton.

The name “peregrine” is derived from the word “peregrination” meaning to travel abroad, roam, or wander, reflecting the wide-ranging movements of this species. One of the more interesting findings of tracking birds during the dispersal period is that although they moved over great distances they did not appear to be aimlessly wandering. Birds were attracted to the grand geologic structures that supported peregrine breeding historically and new structures such as cities that tower over the surrounding landscape. Many of these structures support breeding peregrines today. Dispersing birds were locating and visiting other peregrines over large regions. The questions of how they were interacting with other birds and what they might be learning from the interactions remain a mystery.

Map showing movements of young peregrine falcons from Virginia during the dispersal period. Different colored dots depict different individuals. Data from CCB.

Tracking efforts and other projects are advancing our ability to manage this recovering species in eastern North America. They are providing a wealth of new information that will enable us over time to better integrate peregrine management into the larger conservation landscape. Partners in the tracking effort include the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, National Park Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Virginia Department of Transportation, and Dominion Resources.

Written by Bryan Watts | bdwatt@wm.edu | (757) 221-2247

September 21, 2015