Rappahannock eagles beat expectations

Camellia Satellite Transmitter Has Been Recovered

March 20, 2015Grace Returns to Alligator River NWR Mar 20 2015

March 21, 2015

When bald eagle surveys were initiated in the Chesapeake Bay during the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Rappahannock River was not a standout. Compared to the historic James and Potomac Rivers, the Rappahannock was not as well known to the public. In terms of eagle numbers, the river was overshadowed by the DDT-era strongholds of the upper Potomac, the lower James and the Blackwater. But one has only to look over a map of the tributary to recognize the bones of a thoroughbred. The Rappahannock flows through a landscape that remains relatively low on development and high on natural beauty. The creeks, bluffs, marshes, and meanders combine to make one of the most attractive locations for breeding eagles in the Chesapeake region, and over the past two decades the river has come into its own.

Eaglets in nest looking out over LaGrange Creek along the Rappahannock River. The single pair on this creek during the 1960s and 1970s produced no young in more than ten years. Today, the creek supports five breeding pairs. Photo by Bryan Watts.

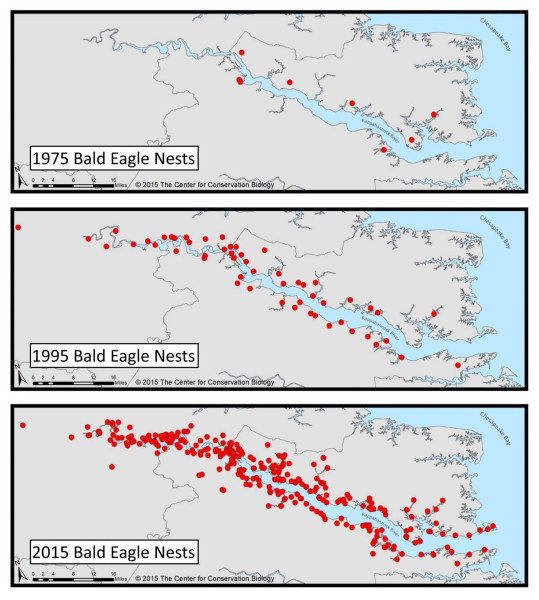

Recovery of breeding eagles along the Rappahannock has been dramatic. By the early 1970s the population had been reduced to six known pairs and the long-standing pair along LaGrange Creek near Urbanna had not produced a single young in ten years. Most of the pairs were located in the lower, salty reach of the river. Over the next twenty years productivity improved, the population increased to more than 50 pairs and birds began to occupy many of the landmarks that today represent hallowed ground. Fones Cliffs, Cat Point Creek, Payne’s Island, Owl Hollow, and Portobago Bay over time have become synonymous with bald eagles in the Chesapeake Bay. Since the early 1990s, the Rappahannock has bloomed and now supports one of the densest breeding populations found anywhere throughout the species range.

The 2015 early survey that includes the Rappahannock was completed on 12 March and documented 219 breeding pairs. Over the past 40 years, eagles have poured into the less salty parts of the river. The 25-mile (40 kilometers) reach of the river just above Tappahannock now supports an incredible 90 pairs. Three locations within this reach support two eagle pairs nesting within 100 meters of each other. Tolerance of territorial neighbors to this degree was never imagined in the early days of the survey and is a testament to the high availability of prey.

A glimpse of an eagle clutch from the survey plane along the Rappahannock River. Adults take short breaks from incubation duties during warm, sunny days. The “egg cup” containing the eggs that helps to facilitate incubation is visible. Photo by Bryan Watts.

Although impacted by the treatment of agricultural lands during the “living better through chemistry” period of recent history, the Rappahannock is now one of the jewels of the mid-Atlantic region. Protection of conservation lands within this watershed will continue to provide a great return on investment.

Adult incubating in large oak tree along Occupacia Creek. This pristine creek is positioned in the heart of the highest eagle density within the Rappahannock watershed. Photo by Bryan Watts.

Written by Bryan Watts | bdwatt@wm.edu | (757) 221-2247

March 20, 2015