Mercury levels in Chesapeake Bay bald eagles

Azalea Returns to Catfish Ponds

July 12, 2010Reproductive effort of red-cockaded woodpeckers at Piney Grove a result of age before beauty

July 13, 2010

Written by Bryan Watts

July 12, 2010

Bald eagle tail feathers representing age classes from young to adult (left to right). Thousands of feathers have been collected over the past 5 years from communal roosts and nesting sites to support ongoing lines of research. Photo by Bryan Watts.

The continued accumulation of mercury throughout the globe has significant implications for human and wildlife health. Mercury is a toxic byproduct of coal-fired power plants and several other industrial and natural processes. Human activities have resulted in a significant increase in the amounts of mercury released into the atmosphere annually. Biological processes transform other chemical forms of mercury into the highly bioavailable methylmercury. Methylmercury is a neurotoxin that has been shown to impact wildlife, particularly those species that rely on aquatic food chains. The accumulation of mercury in fish has been well-known for years, and has lead to consumption advisories in 46 states that warn people to limit or avoid eating certain species of fish.

Due to their almost complete dependence on aquatic prey, bald eagles are vulnerable to mercury and represent a good indicator species for mercury levels within aquatic systems. Blood mercury levels in some northern populations have been associated with reduced reproductive success. However, no efforts have been undertaken to examine mercury levels within the Chesapeake Bay population. Since mercury levels will continue to rise for the foreseeable future, such an investigation would provide a benchmark for future comparisons.

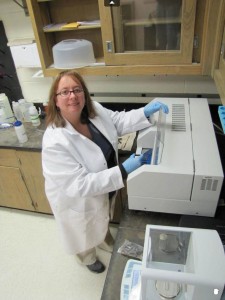

Samples of dried feathers are snipped and prepared for analysis in a Direct Mercury Analyzer (DMA). Photo by the Center for Conservation Biology.

Shed feathers are the least invasive means of assessing mercury loads in birds. Mercury is laid down in feathers only during the period while they are growing and have an active blood supply such that feathers reflect mercury exposure during the molting period for adults. In the Chesapeake Bay, feather molt occurs most intensely during the latter stages of brood rearing and just following the breeding season. Over the past 5 years, Center biologists have visited nests opportunistically after the breeding season to collect recently shed adult feathers as part of a population genetics study. During this time, we have collected feathers from 83 nests scattered throughout the Chesapeake Bay.

Leah Gibala Smith analyses the feather samples using a DMA (Direct Mercury Analyzer) in Dan Cristol’s lab in the William and Mary Biology Department. Photo by the Center for Conservation Biology.

CCB researchers teamed-up with Dan Cristol’s lab in the Department of Biology at the College of William and Mary to use a portion of these feathers to assess mercury loads in Chesapeake Bay eagles. Over the past several years, Dan Cristol and graduate students have produced a large body of research on the impact of mercury on a wide range of bird species. It has been a great opportunity to partner on this investigation.

Feathers from adult bald eagles nesting on the Chesapeake Bay had the lowest mercury levels ever reported for a population of this species with the average value less than 4 ppm. Mercury levels in most individuals were below all cited thresholds of concern for sub-lethal effects. These results are consistent with the productivity estimates within the Bay that are some of the highest reported throughout the breeding range. Sampling species of conservation concern for contaminants can be expensive and invasive. This study also illustrated that collecting molted feathers from beneath bald eagle nests provides an estimate of mercury concentration that was sufficient to assess whether the population is experiencing exposure to levels of mercury stated to be harmful in the literature on birds. Despite considerable variation between individual feathers, collecting >4 feathers from individual birds should suffice to provide an estimate that is within 10% of the value of that bird’s plumage. In this case, expensive and invasive sampling of blood or other tissues is not warranted given the utility of sampling molted feathers.