Studies reveal Black Rail populations in the Chesapeake Bay are nearing extirpation

Sea-level rise and tidal freshwater marsh birds

March 8, 2010Azalea returns to Mattamuskeet NWR in NC

March 9, 2010

Written by Michael Wilson

March 9, 2010

The black rail (Laterallus jamaicensis) may be the most endangered bird along the Atlantic Coast. Populations have been declining along the Atlantic coast for over for over a century, but reductions during the last 10-15 years appear to be more rapid and devastating. Recent evidence suggests that black rails may only breed in a dozen or fewer places in each state along the Atlantic Ocean. Although population changes over this period appear to be pervasive, they are particularly pronounced throughout the mid-Atlantic region. Over the past 10-20 years, populations of black rail in Virginia and Maryland have declined more than 75% and have become dangerously low. There has been a reduction in both the number of breeding locations and a loss of individuals from historical strongholds. The reasons for the dramatic decline of the black rail are not completely understood, but may be attributed to factors such as habitat loss and degradation, predation, low reproductive rates, overwinter survival, and environmental contaminants.

Black rail walking through a salt marsh. Photo by David Seibel.

The Center for Conservation Biology initiated a study in the summers of 2007 and 2008 to determine the current status of the black rail in coastal Virginia. Prior to this study, the distribution of black rails in coastal Virginia had never been systematically determined. Information on the species’ occurrence only existed in the form of anecdotal accounts and a small collection of unpublished historical records. These accounts generally characterized black rails as being patchily distributed within tidal salt marshes on the eastern shore of Virginia including the barrier islands, but its overall distribution within this region was poorly known.

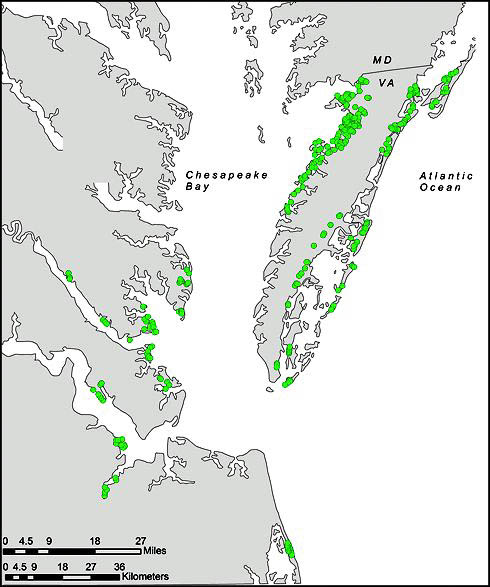

We established a network of 328 survey points within marshes throughout coastal Virginia, containing historical occurrence records for black rails and marshes with appropriate habitat. Surveys were conducted at night by water and road access. Most surveys were conducted between the hours of midnight and before sunrise because this is the time that black rails call most consistently in this region. Surveying marshes by boat was made more challenging than our other marsh studies because of the difficulty of navigating near shore areas under dense nighttime fog.

Black rails were only detected at 12 of 328 survey points (< 4 % of total). All positive detections were restricted to the bayside marshes of Accomack County on the Delmarva Peninsula. No black rails were detected within other survey areas such as the seaside of the Delmarva Peninsula, the Barrier Islands, the western shore of the Chesapeake Bay, along the James, York or Nansemond rivers, or Back Bay.

Of the 328 survey points (green circles, many overlapping) in Virginia, Black Rail were only found on the bay side of the Delmarva Peninsula within the two year study. Map by the Center for Conservation Biology.

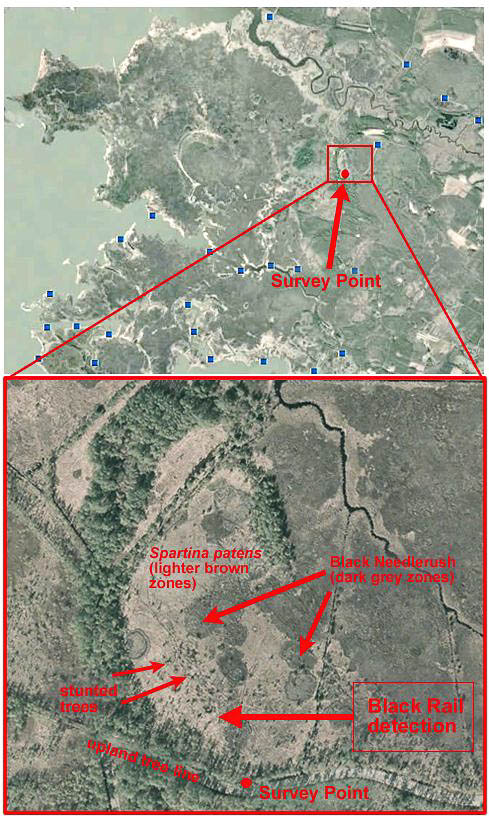

The location of all black rail detections shared 4 primary characteristics: 1) being within the high marsh zone, 2) near the upland edge, 3) within a zone of scattered red cedars or stunted pines, and 4) only where the adjacent upland matrix was composed of a block of pine forest. Black rails used the highest elevation areas of salt marshes composed primarily of a cover saltmeadow hay (Spartina patens), saltgrass (Distichlis spicata), and black needlerush (Juncus romerianus).

Example of black rail habitat on the Eastern Shore of Virginia – high marsh, grasses with scattered trees/shrubs, near the upland tree line. The blue points indicate other black rail survey points. Map by the Center for Conservation Biology.

Based on observed occupation patterns, black rails appear to only be found in a mere fraction of the available habitat. We examined aerial photographs of all survey locations to find considerable overlap in the vegetation conditions of used and unused marshes. It is unclear why certain marshes support black rails, whereas many other marshes of similar vegetation composition do not. These patterns may suggest that factors other than vegetation may be responsible for recent changes in their distribution and population size.

Black rails appear to have retracted completely from their historical distribution along the seaside of the Delmarva Peninsula. Moreover, known population strongholds on the bayside at locations such as the Saxis Wildlife Management area have been dramatically reduced compared to past accounts.

The timing of our study coincided with another survey for black rails conducted in Maryland by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources. Survey teams in both states used the same protocols such as visiting marshes at night, the time duration for counts, and even using the same call-response broadcasts. Sharing survey protocols between the two states allows for direct comparisons of results. Maryland surveys revealed that the number of locations black rails were detected had declined by 85% compared to their previous surveys in 1992.

Overall populations appear to be dangerously low and may be at a risk of extirpation in the Chesapeake Bay region. The future of this species is uncertain because black rails occupy habitats that are vulnerable to land-use change, in close proximity to upland nest predators, and sensitive to changes in climate and sea-level rise.

The Center has initiated an Atlantic and Gulf coast working group to partner with agencies and biologists in developing a strategy for the conservation and management of black rails.

For more information visit the Eastern Black Rail Conservation and Management Working Group

Project sponsored by the Center for Conservation Biology (CCB) and Virginia Department of Game & Inland Fisheries (VDGIF).