Red knot resight data indicates flux between two migration staging areas

Investigation of shrubland migrants on the Eastern Shore of Virginia NWR

September 3, 2009Flexibility of cormorant and pelican diet assemblages

September 5, 2009

Written by Bryan Watts

September 4, 2009

The rufa subspecies of the red knot has declined precipitously over the past 2 decades leading to its listing as an endangered population in Canada its declaration of endangerment by the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Animals, and a petition for endangered status in the United States. Evidence for the decline comes from long-term surveys of Delaware Bay and the largest known overwintering site at Tierra del Fuego. In the span of only 30 years, the estimated population has declined from 100,000-150,000 to possibly below 30,000.

A red knot, just before its release. Photo by Bryan Watts.

Most research that has concerned possible explanations for the population decline has focused on the foraging conditions within Delaware Bay. Delaware Bay is a terminal, spring, staging site where birds refuel before moving to their breeding grounds in the high arctic. Birds staging within this site feed nearly exclusively on eggs of the horseshoe crab, and egg densities have been related to foraging rates, rates of mass gain and the associated ability of birds to reach threshold leaving weights. Leaving weights have been suggested to influence adult survivorship forging a link between the conditions within Delaware Bay and recent population declines. Horseshoe crabs have been harvested commercially in Delaware Bay for decades but the rapid emergence of the conch industry has dramatically increased harvest pressures in recent years. Claims that harvest rates are impacting the strength of spawning events, resulting in egg densities well below those required by staging knots have lead to conflicts between the fishing industry and conservation groups.

Red knots foraging in the surf, several wearing leg tags for resight identification. Photo by Barry Truitt.

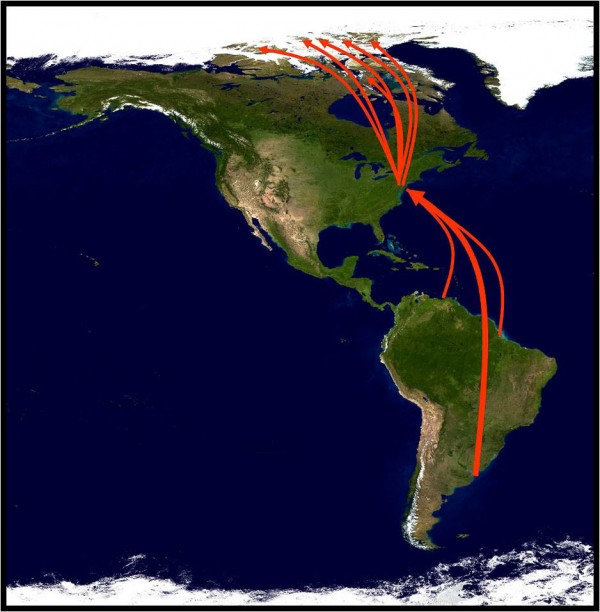

The Virginia Barrier Islands are approximately 180 km south of Delaware Bay along the outer Atlantic Coast. The islands support significant numbers of red knots during spring migration but host no meaningful spawns of horseshoe crabs. Red knots staging along the islands feed on bivalves within the intertidal zone. CCB along with The Nature Conservancy has been flying aerial surveys of shorebirds along the island chain during spring migration since 1994. Beginning in 2006-2007 with funding from Virginia’s Coastal Zone Management Program, CCB biologists have been investigating the stopover ecology of red knots using band resights. Biologists searched flocks of red knots and identified 277 individual birds that carried flags with unique alpha numeric codes. These birds were tracked to the country where they were banded, including Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Canada, and the United States. With funding from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, we resighted red knots again in 2009 and will continue this coming spring.

To date, we have observed 562 uniquely marked red knots in Virginia. These marked knots were originally banded in the United States (53%) during migration or during winter in Tierra del Fuego (45%). This indicates that a substantial portion of the knots that use Virginia are long-distance migrants from Tierra del Fuego. Suprisingly, we found that 49% of knots observed in Virginia have also been observed in Delaware Bay between 2005 and 2009. This includes 326 movements between these spring stopover sites from year to year and 88 movements that occurred within a given year. Preliminary analysis of this data suggest that in some years, movements of red knots from Delaware Bay to Virginia within a given spring migration may equal the number that move from Virginia to Delaware Bay. The finding that birds are moving between these two staging areas implies that the migration ecology of this population may be more flexible than previously thought and highlights the importance of the entire mid-Atlantic Coast for this declining species.

Map of red knot migration routes, stopping by the Eastern Shore of Virginia. Photo by the Center for Conservation Biology.

CCB has now committed to working with researchers from Delaware Bay to complete more detailed analyses of the movement of red knots through Virginia and Delaware Bay during Spring. We expect that this analysis will allow us to determine the rates that knots move between each spring stopover site within and between years. We are also quite hopeful that we will be able to estimate the relative contribution of each stopover site to the survival of knots. Understanding these dynamics is vital to developing conservation strategies to reverse recent declines in this species of shorebird.

Project sponsored by The Center for Conservation Biology (CCB), the National Fish & Wildlife Foundation (NFWF), The Nature Conservancy (TNC), and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS).